Chinese internet as an identity

on Xiaohongshu (read: Red Note), the subjectivity of language, and community-building vis-à-vis social media (platforms)

You don’t need more words from me to describe how popular the Chinese app Red Note, or Xiaohongshu, has become overnight.

I woke up on Monday to my feed full of content like “TikTok refugee here, AMA.” Almost every mainstream media now has a headline about it. Consumer brands spared no time to make their social teams come up with marketing campaigns targeting the #refugees.

It’s a rare moment in the history of the Chinese internet where you saw non-Chinese speakers move to a non-localized, solo-version platform en masse. Celebrities, sure; brands, fine. They have been on XHS, a platform known for its marketing potential, forever. But the average, curious, somewhat clueless TikTokers paying their “cat taxes” and populating #tiktokrefugees? If you are a long-time XHS user like me (my 2024 XHS wrapped told me that I was on the app 364 days last year), it’s hard not to feel like worlds are colliding and collapsing a little bit.

While all this was happening, I quickly found myself missing my usual algorithm. One self-introduction post is cute and funny, but several in a row, each getting a large number of likes and comments, quickly diminished the pleasure of viewing1. Granted, part of this is being conditioned by social media so deeply that all I crave is the instant serendipity from fast, infinite scrolling.

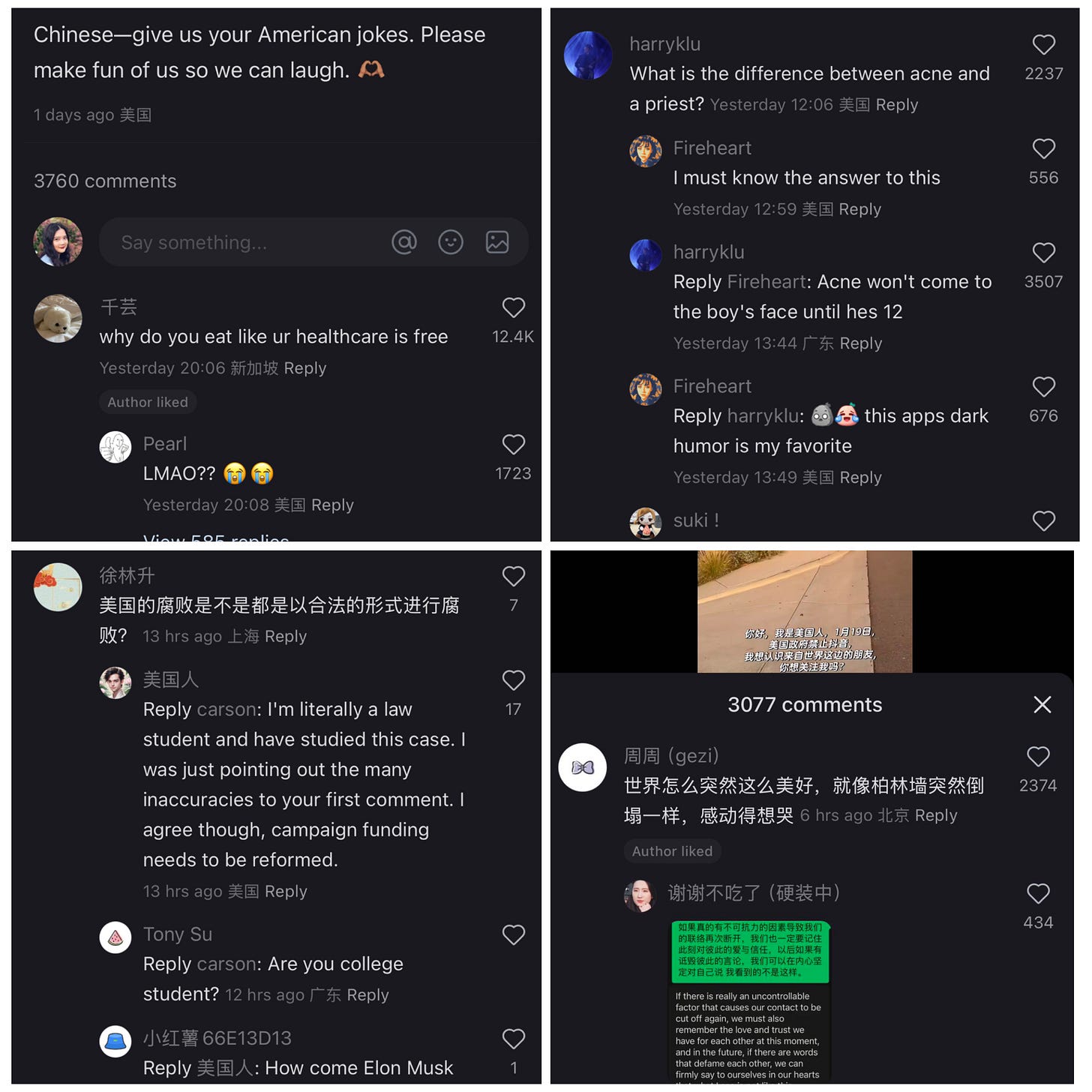

But there’s more. In an XHS post titled “Please defend the subjectivity of the Chinese language amid the refugee wave,” a user wrote, “native English speakers have enough privileges already, and they don’t need another one: Coming to a Chinese app and making existing users communicate with them in English. … We are no longer the kids that our parents pushed to practice speaking English whenever we see foreigners.”

While the overall reception of more English content on XHS is positive, I’ve been seeing quite a few thoughts like this. On the surface, it’s a natural, intuitive response to a hegemonic language that invaded a space that was deemed private by many (even though it’s a social media platform—more on this later). On a deeper level, I see this as rooting in a lifelong experience growing up on the Chinese internet.

What does it mean for someone, working and living in a world with a language that is not their own, to be on an enclosed — even secretive — social media platform?

Community-building in the dark

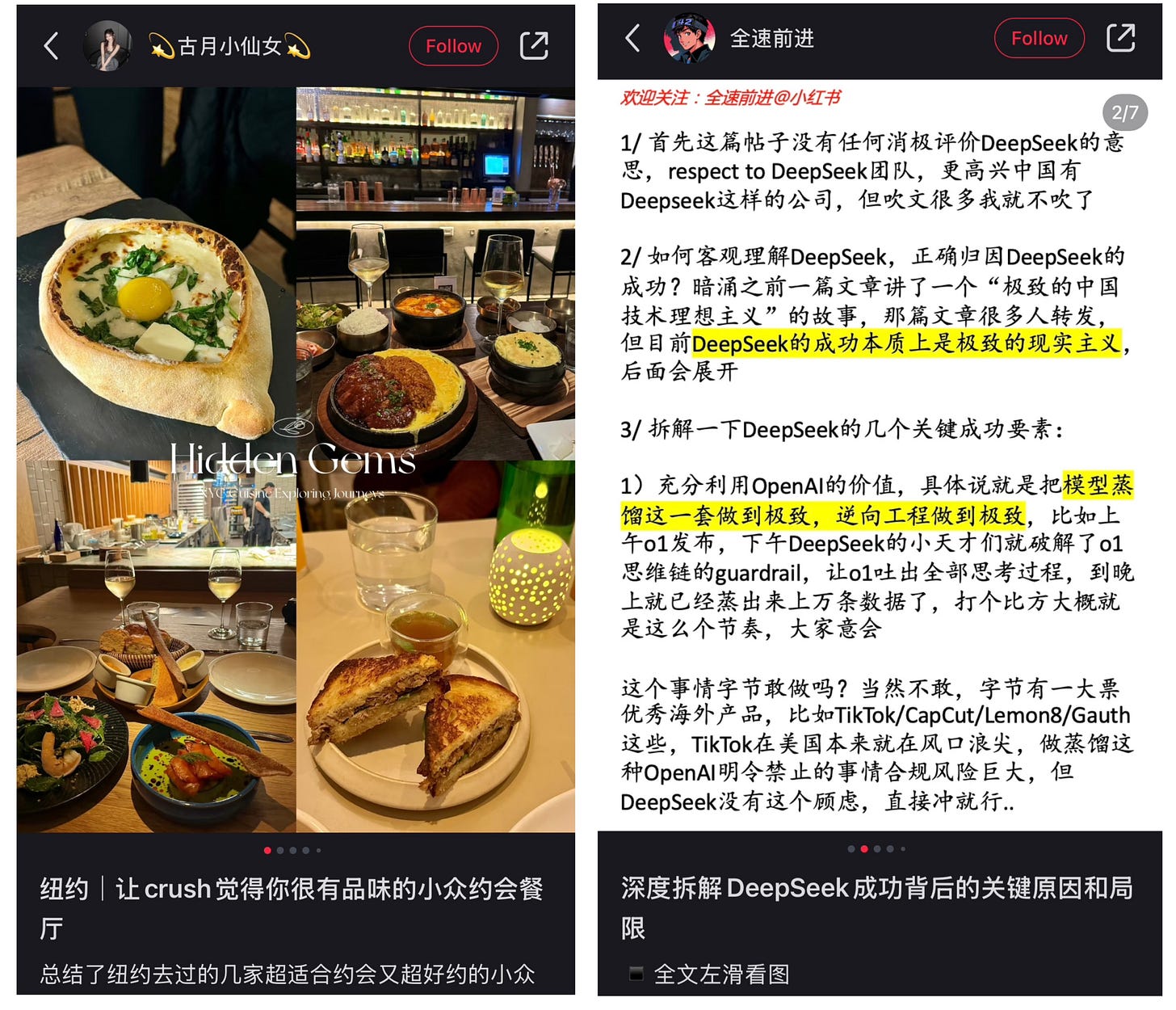

Back in the beginning of 2024, when the threat of a TikTok ban wasn’t imminent, I talked to a long-term product executive about why there couldn’t be an app like XHS in the US. His argument, which I agreed, was that XHS is a platform that targets a very specific demographic: women in their 20s and 30s who, if not affluent, live a reasonably comfortable life in first and second-tier cities in China. That is not the main demographic of any platform in the US. When ByteDance launched Lemon8 (an XHS copycat, if you will), the aesthetics of the app appeared to be catering to this group of people, but Lemon8 never took off beyond high download volumes.

It’s a special demographic that makes XHS different. At the very least, women feel a little safer here than on other platforms like Weibo and Douyin. With tags like #宝宝辅食 (#BabySolidFood) and pseudonyms like “Momo,” the users curated a space to share real-life experiences without fear of misogyny and judgments. This is also the birthplace of various forms of feminist advocacy, as well documented in academic research.

To be clear, like all social media platforms, XHS is never an idyllic, safe space, nor does the company want to do so (it’s commerce, baby). But as a result of user-driven algorithm hacking and, ironically, content moderation on the Chinese internet, XHS became a filter bubble that fosters subcultures.

Of course, calling XHS a platform only for young, rich women is a stretch. After all, it’s an app with 300 million monthly active users and is broadly seen as a search engine. I know people call TikTok Gen Z’s search engine, but boy XHS is just so much better — who needs Eater when you have this app? The most addictive part is how much people are willing to share, from standard restaurant reviews to notes app dating stories. I once followed an account that shared how their rental apartment turned into a scam that involved a college professor and his mistress. It’s Reesa Teesa before Reesa Teesa, and I’m here for it.

But the point is, none of this will be possible without what the Chinese internet has been like for years: Behind the firewall, the enclosedness of it all turned the platform into an enclave. It’s a public yet intimate space shaped by a shared understanding that, so long as the wall still exists, let’s thrive and make the most of it.

What made this all that more tolerable and sustainable is that the technology is actually good. Due to censorship and internet regulations, Chinese tech companies were confined in terms of where they could innovate. And to compete, these companies were forced to quickly come up with new product designs, better recommendations, and useful features that keep users there (My friends at the American Roulette explained this more in-depth.) I’d argue that the same goes for content creators. Ultimately, Xiaohongshu is a platform where more creative and more niche content wins.

Today’s XHS is experiencing a conundrum: Part of the fun came from interacting with an existing user base — that it’s not really a platform cold starting — yet these users don’t want XHS to become TikTok. In some ways, they are the exact opposite of each other and represent different parts of our identities. Xiaohongshu is and likely will always remain a Chinese platform, for better or for worse — as we have already seen reports about how the company’s employees were walking a fine line navigating the influx of users and content moderation.

Cultural exchange is a beautiful thing

I am in no way saying that the interactions between American TikTok users and Chinese XHS users are not valuable. In fact, I’m seeing a lot of rich discussions that I have never imagined myself living to see.

In one post, a healthcare worker asked what the healthcare system in China was like, and received responses from a physician at a public hospital, a nurse, and people who went above and beyond to find data that shows how much Chinese people spend on healthcare. In another case, an American user wanted to know how Chinese people pay taxes with a machine-translated question.

Some users compared this phase of the internet to pandemic darling Clubhouse, but more said that they were reminded of the early 2000s internet. Once upon a time, there was a site called ICQ.com, where you could connect with random strangers on the internet. Everyone rushed to download MSN. You could still access Google from China. It was a fever dream that got everyone emotional.

Despite the rise of what’s known as Chinese Twitter and accounts like Teacher Li, the number of Chinese users who could/want to access the global internet today is still minimal. Conversely, what’s really special about the digital migration from TikTok to XHS was that the people who participated were real — and in tech lingo, scalable.

So I don’t think the question is whether XHS is the Chinese TikTok or whether XHS is the alternative. I won’t get into how TikTok and XHS are completely different apps here, as I believe it has been written extensively from both a product and a business perspective. I do think, however, that the #tiktokrefugees are probably aware of that, which is why this act of protest likely won’t last long. In a way, though, it does make this exodus all that more symbolic.

Let’s have fun while we are here.

If you’d like to read more about XHS beyond the headlines:

A group of early career researchers studying Chinese social media platforms compiled this reading list about “Engaging with Xiaohongshu.”

Garbage Day dug up who started the great XHS migration.

Chaoyang Trap, which imo started the genre known as XHS reporting.

Hello. If this is the first time we meet, I am a freelance reporter and writer. Usually, I write about things like finance and technology. Here, I try to not think about these topics but rather focus on a more personal reflection. I wrote this based on my experience and conversations with others (all opinions are my own), but I also want to hear what you think. Send me a note: ylu22 [at] proton [dot] me. Welcome.

It’s not a secret that XHS heavily prioritizes the initial posts by new accounts, as well as posts that are not usually seen on the platform, hence English-language content got a few days of boost.

Great article!! Thank you!

this was so interesting to read - thank you for sharing your thoughts! somewhat unrelated, but this post made me think about a site called wenxuecity, frequented often by my mom, who immigrated to the US from china in the 90s in her early twenties. from my perspective, she seemed to use it all the time, often to communicate with other chinese moms. it had the vibes of an early 2000s Internet forum - definitely not as slick as xiaohongshu - but i suspect that the site was vital to her and other immigrants of her generation! I’ve only read one piece about it - linked below.

https://eliqian.substack.com/p/echoshadow